On a recent trip to Belgium, I was struck not only by the depth of the country’s private art collections, but by how thoughtfully they’re being shown in dialogue with public ones.

At the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, the exhibition Collected with Vision: Private Collections in Dialogue with the Old Masters places contemporary works from private collections alongside the museum’s permanent holdings. The result is fresh, thoughtful, and sometimes even startling.

These six works—each part of the museum’s permanent collection—stood out to me not just for what they are, but for how they’re currently framed within new conversations across time and genre.

This wall offers a chorus of conflict—spats, arguments, moral breakdowns—captured with theatrical detail in Jan van Amstel’s Tavern Scene and neighboring Flemish genre paintings. The figures in the paintings are animated, entangled, sometimes ridiculous.

Above them, two sculpted men by Juan Muñoz sit suspended in folding chairs, legs casually crossed, seemingly laughing at it all. At first, the juxtaposition feels light. But, are the Muñoz figures amused... or avoiding something? When faced with daily or moral chaos, do we fix it, challenge it—or step back and minimize it with humor? The grouping doesn’t answer that question. But it does remind us that being an observer is never truly neutral.

This grouping stopped me—quietly, and then completely.

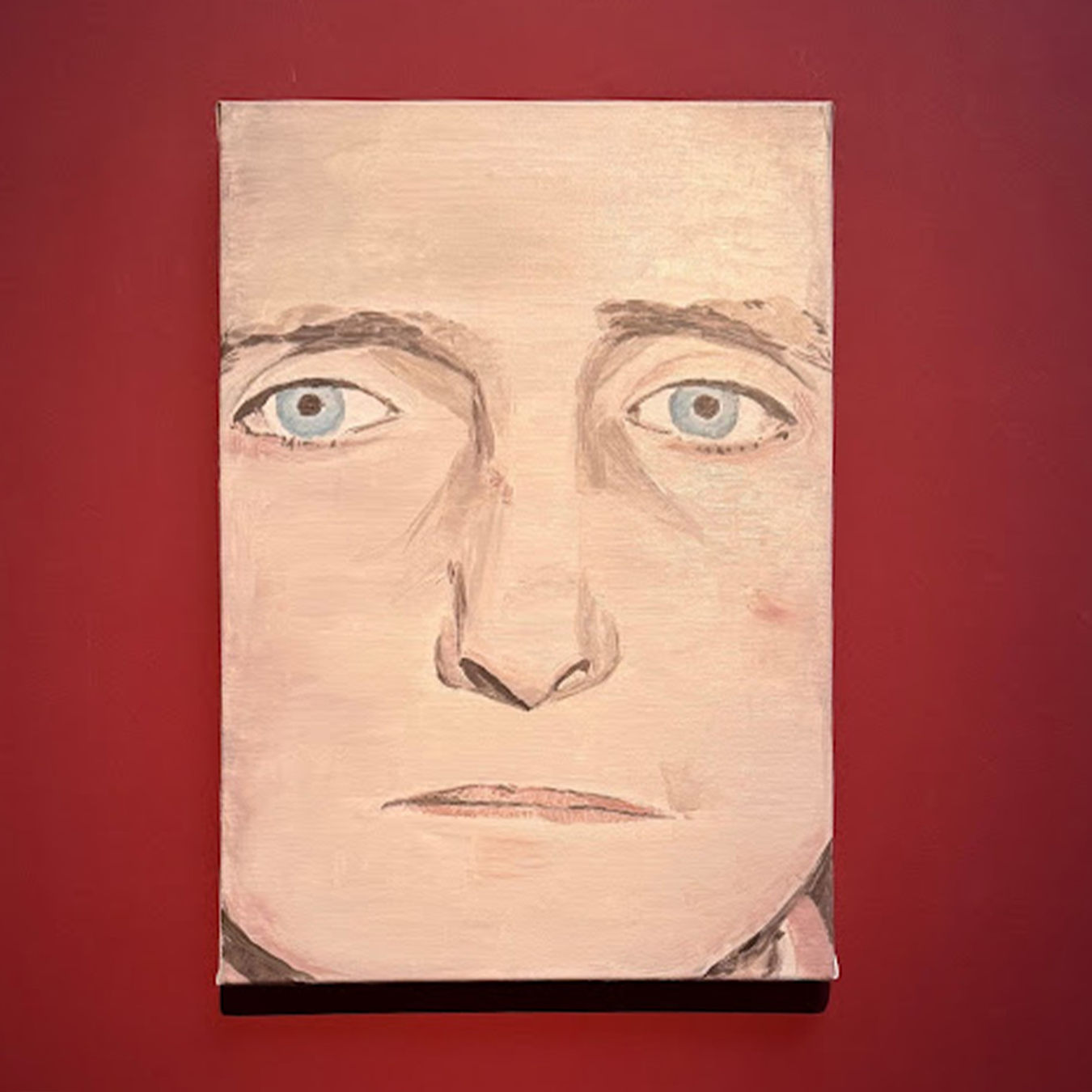

Fouquet’s Madonna is otherworldly: her porcelain skin, jewel-like setting, and stylized detachment create a vision of divine perfection. When placed alongside Rineke Dijkstra’s raw postpartum portrait, Marlene Dumas’s vulnerable figure, and Luc Tuymans’s cool, uncanny gaze, the sacred meets the human. Or perhaps the human becomes sacred. I was reminded that how we frame art—literally and metaphorically—can shift everything we see.

This was one of the most powerful moments in the museum.

Rogier van der Weyden’s painting is composed and luminous—a devotional image that contains suffering within the structure of faith. Berlinde De Bruyckere’s sculpture, wrapped tightly around a rusted pole, feels raw, collapsed, undone.

The pairing doesn’t just mirror Christian iconography—it unsettles it. I stood there thinking about how the body carries both belief and pain—and how artists across centuries return to it as the most honest site of meaning.

Memling’s angels sing and play in radiant devotion, their harmonies implied in every painted gesture. Nearby, Olafur Eliasson refracts light through a sculptural lens, casting a warm beam across the gallery floor—as if pulling light straight from the canvas into space.

And then there’s the yellow guitar on the wall: playful, almost absurd, but undeniably present. I appreciated how music by The Velvet Underground (one of my favorite bands) audibly playing in the gallery was both incredibly odd and yet added so much and kept me company as I continued to watch the light behave like something was just about to happen. The moment felt suspended, like art holding its breath.

James Ensor’s masks are never just masks. They reveal and distort, entertain and accuse.

In Intrigued Masks, a crowd of carnival faces presses toward the viewer—some laughing, others leering, none truly readable. It’s theatrical and unsettling all at once.

The Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp holds one of the most important collections of Ensor’s work, and the dedicated gallery is reason enough to visit. Standing among these works, I was reminded that sometimes the most honest art doesn’t show the face—it shows the mask.

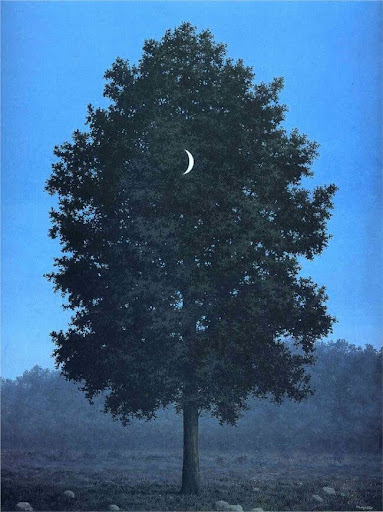

Magritte invites us into a world where logic bends, but gently.

In The Sixteenth of September, a single tree stands still in twilight, its branches perfectly framing a floating crescent moon. It shouldn’t make sense—but it does, completely.

The image feels calm, even sacred, like a secret shared between nature and dream. I stood in front of it longer than I expected, watching the moment hover—timeless, improbable, and strangely true.Art reveals more when we notice how works speak to and connect with each other—and what works–on their own or collectively–awaken in us in the moment.